For more, visit the artist’s website.

By Angela Kohout

The work of Linda Dement holds a mirror to the monstrously grotesque underbelly of femininity- in her own words, “giving form to the unbearable,” (Dement 1). Dement’s computer-based interactive works, including 1991’s Typhoid Mary, 1995’s Cyberflesh Girlmonster, and 1999’s In My Gash are examples of Dement’s presence as a pioneer of cyberfeminism, weaponizing the female body to distort preconceived notions of gender through the use of the yet-undefined realm of cyberspace.

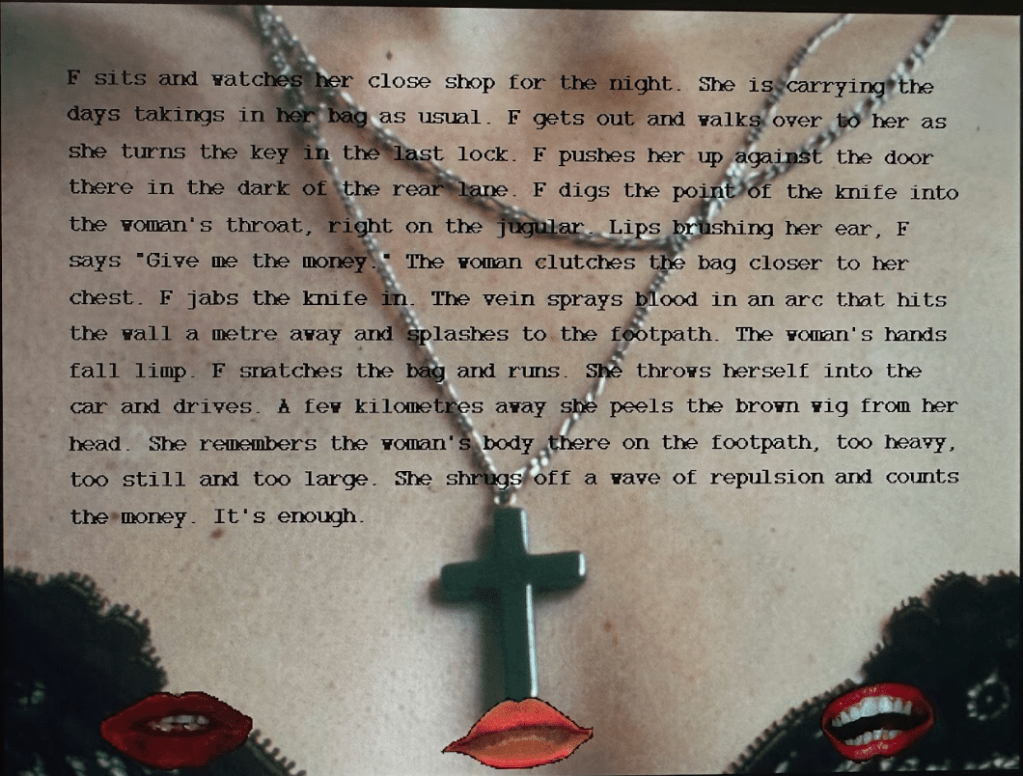

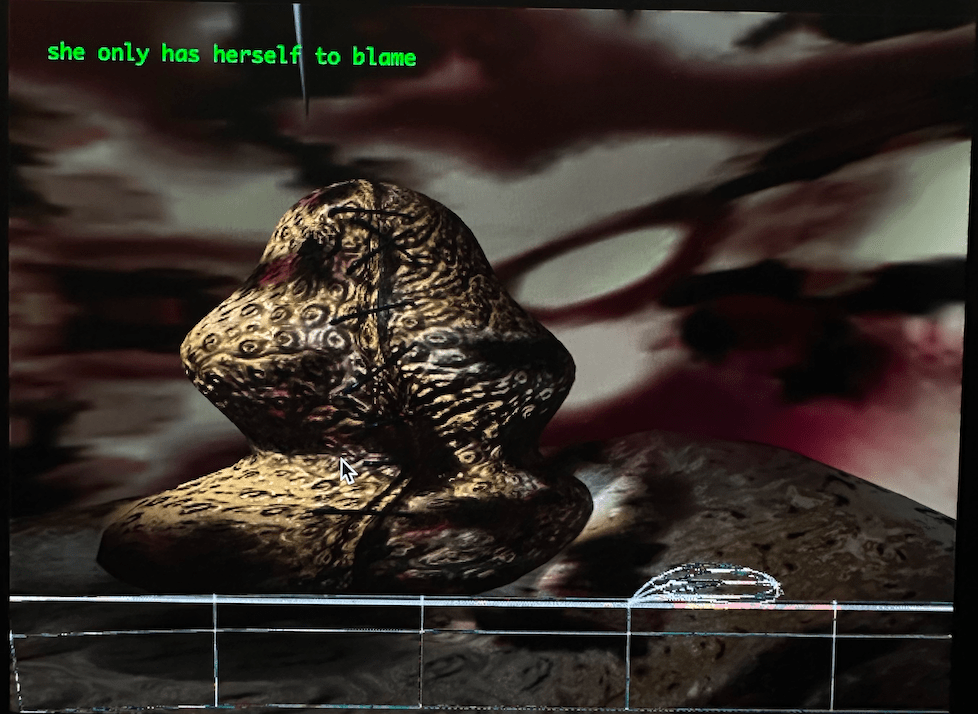

The “monstrous femininity” of Linda Dement’s work is seen most explicitly in Cyberflesh Girlmonster. Thirty attendees to the Adelaide Film Festival voluntarily scanned body parts of their choice, which Dement then crafted into the eponymous “girlmonsters”, for the user to click on and interact with- the bodies are collaged into startling forms crafted from the ears, breasts, and fingers of these volunteers. Both the narratives attached to the bodies and the bodies themselves are cruel and graphic- the blunt language of the written narratives evokes a certain brutality that Dement describes as “…a macabre comedy of monstrous femininity, of revenge, desire and violence,” (Dement 2). Addiction, necrophilia, and suicide are brought up as casually as the weather in this piece. The bodies and their narratives are randomized with no controllable interface, with the computer-based technology of Cyberflesh Girlmonster mirroring the content in the nebulosity of its form(s), and the aggressive confrontation of its content.

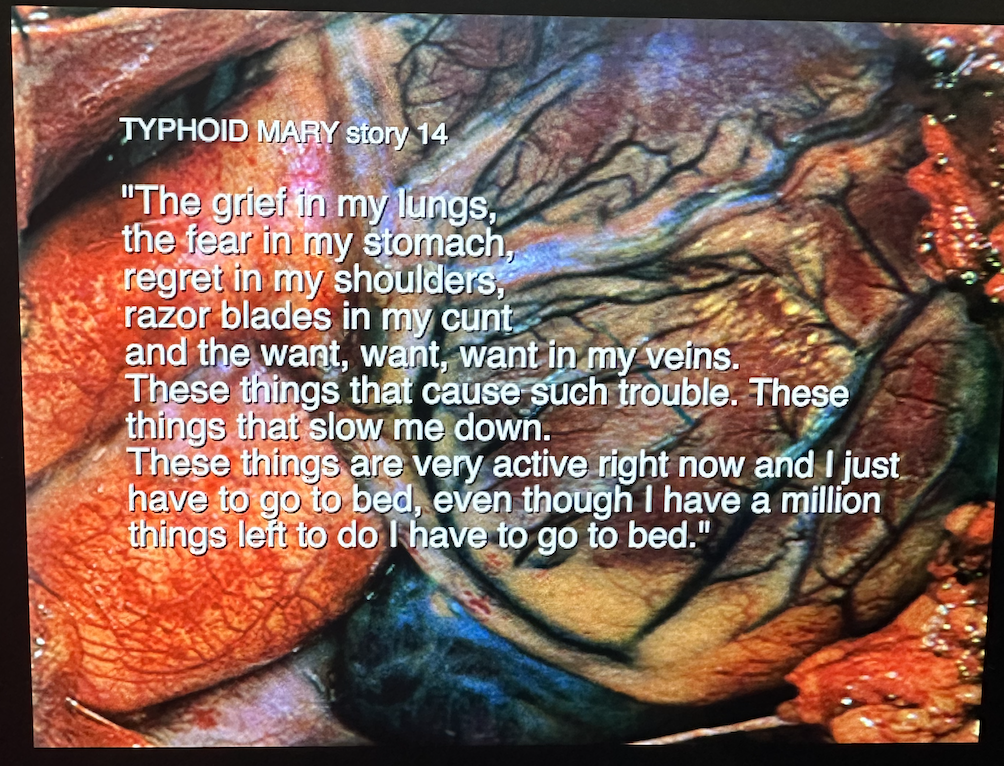

Typhoid Mary and In My Gash offer more personalized perspectives on the monstrous feminine, with both works loosely based on central fictional characters. Typhoid Mary’s imagery is also comprised of collage, meant to invoke feelings of surgery on the psyche (Tofts 120) as the user familiarizes themself with the titular Typhoid Mary’s relationships with sexual pleasure and violence. The work contains printable stories, clinical facts about typhoid fever, and a garish, cluttered aesthetic that suggests a certain inseparability between the needs of the physical body and the desires of the psyche, no matter how perverted, violent, or clinical.

In My Gash purposefully plays on the title’s double entendre to situate the viewer in the unnamed subject’s body, instead referring to her in the game’s opening credits as “Lying Ugly Mess Bitch”. The viewer navigates through the four titular “gashes”, experiencing her life through a third-person gaze made even more voyeuristic by the on-screen pop-up videos that further flesh out the main character’s life. The language of the work is important, drawing a clear distinction between the modality of being a witness to the events depicted in In My Gash, vs a voluntary participant on a journey to self-discovery. This lack of consent of both parties is of key importance to the violence of this work- the form and structure of In My Gash support Dement’s use of the violent and grotesque to forcibly visualize the “unbearable” aspect of femininity.

As they relate to media archaeology, Dement’s work aligns with its principles of recontextualization and reflection- specifically in “…shaping human perception and cultural norms,” (Mulaiee, 3). Dement’s embracing of cyberspace as a place of creativity and expression rather than one of control is reminiscent of the work of other cyberfeminists of her time- utilizing the new tools and technologies of the digital era to rewrite their female experience in a yet-undefined, but still binary, space. Linda Dement forces her viewers to be unwilling voyeurs to her cruel and uninviting world of female monstrosity, both embracing and degrading her otherness in equal measure to challenge what it means to be “feminine”.

Works Cited

“Australian Video Art Archive.” Linda Dement | AVAA, 2003, http://www.videoartchive.org.au/ldement/index.html.

Dement, Linda. “Linda Dement.” Linda Dement – Cyberflesh Girlmonster, 2020, http://www.lindadement.com/cyberflesh-girlmonster.htm.

Muliaee, Maryam. “Media Archaeology and Art: An Exploration of Past, Present, and Future.” The Journal of Media Art Study and Theory, vol. 5, Aug. 2024, p. 3

Tofts, Darren (2005). Interzone: Media Arts in Australia. Victoria: Craftsman House. p. 120