Killer.berlin.doc by Bettina Ellerkamp and Jörg Heitmann (1999)

An experimental film with the technology and aesthetic intersecting documentary, fiction, and game.

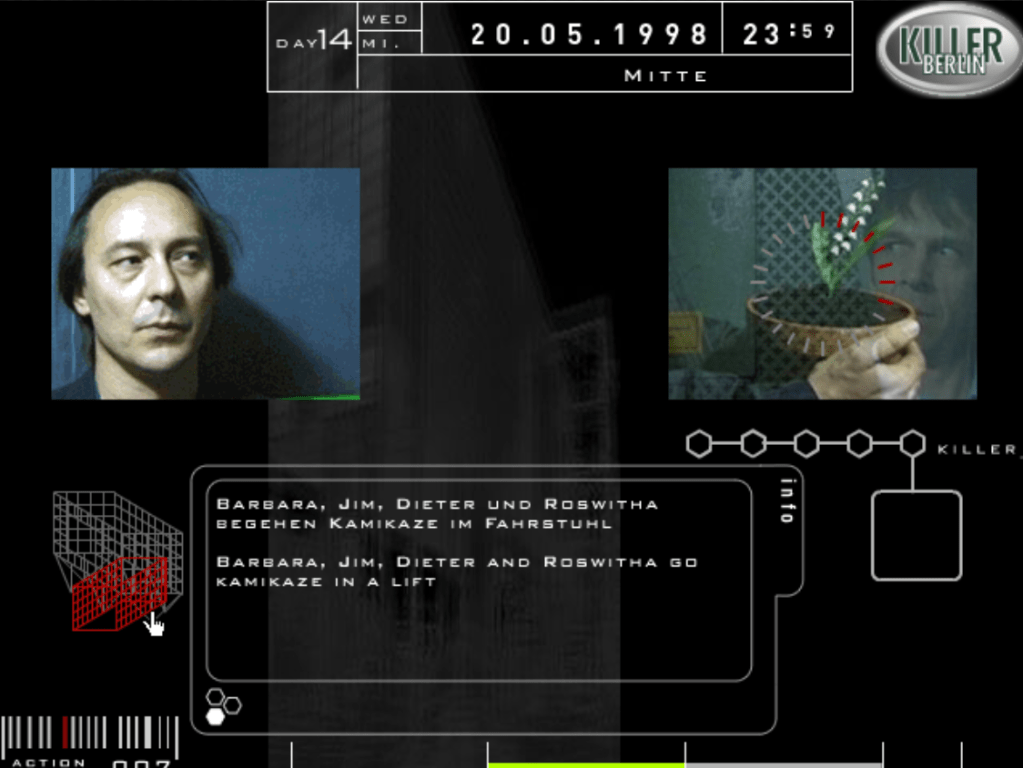

Synopsis: In May 1998, ten people, wanting to talk about their lives in a changing city, decide to turn their lives in Berlin into fiction. They play killer, a game in which no one knows the others, and each person is perpetrator as well as victim. The task is to find a person, designated but unknown to the player, and to plan the perfect murder for the victim. Knowing that at the same time yet another person is searching for him or her, the player looks for the designated victim. The players create a web across the city; the paths they take, the places they visit and their encounters with people all draw a subjective sketch of contemporary life in Berlin in the ‘interim’…

View more details about the film at:

Our mural board summarizing the different elements of the complex project https://app.mural.co/t/newyorkuniversity8996/m/newyorkuniversity8996/1728788402884/b3f04851f4d4c27037798b1c72379d8db2b63c96

http://www.bunnies.de/bunnies/killer.htm

https://www.arsenal-berlin.de/forumarchiv/forum99/killer.html

From the Interactive Cinema book:

A noteworthy example of interactivity as a tool for mediating borders is the German film Killer.berlin.doc, a visionary yet rarely analyzed docufiction multimedia project that captures a multicultural group of real-life artists who sign up to play an improvisational version of the children’s game “killer.” In the game, each participant is assigned another player to “kill” using makeshift symbolic weapons such as letter bombs. The group of artists hail from different places, including East and West Berlin, England, Japan, and the U.S. Reimagining Berlin as a real-life playground proves to be a suitable metaphor for a city-in-transition and an appropriate allusion to the improvisational period of identity figuration that succeeds the collapse of geographical borders.

Killer.berlin.doc was originally shot on digital video and then printed to 35mm film, resulting in a hybrid type of cinematography that lies in between analog and digital–a phenomenon I call “composite aesthetics.” This “un-digitization” was made for the film to be eligible for submission to the Berlinale Film Festival, which did not at the time accept digital formats. The film’s title thus became consequently ironic since it alludes to the film’s “computerized” name (as a .doc file) rather than the standard analog format of its festival version. For this chapter, I would like to focus on the film’s subsequent adaptation into an innovative web interactive version that was unfortunately too far ahead of its time as a piece of future cinema, much like Chris Marker’s brilliant 1998 interactive CD-ROM Immemory, which utilizes the mechanisms of interactivity as psychic and mnemonic prostheses.

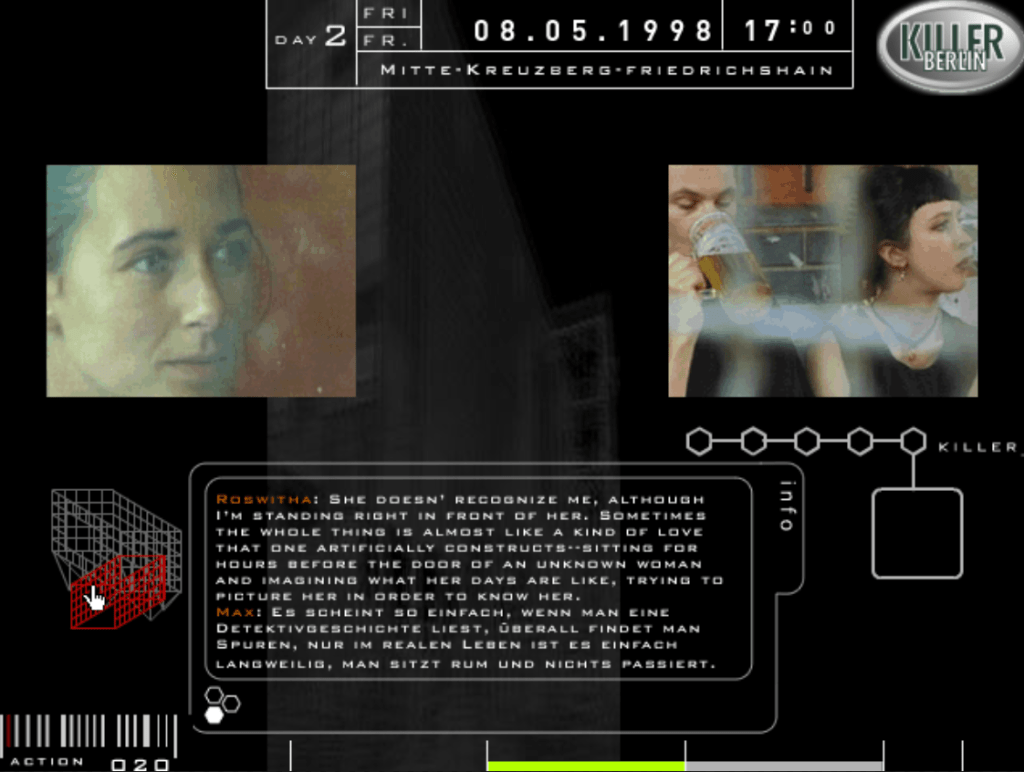

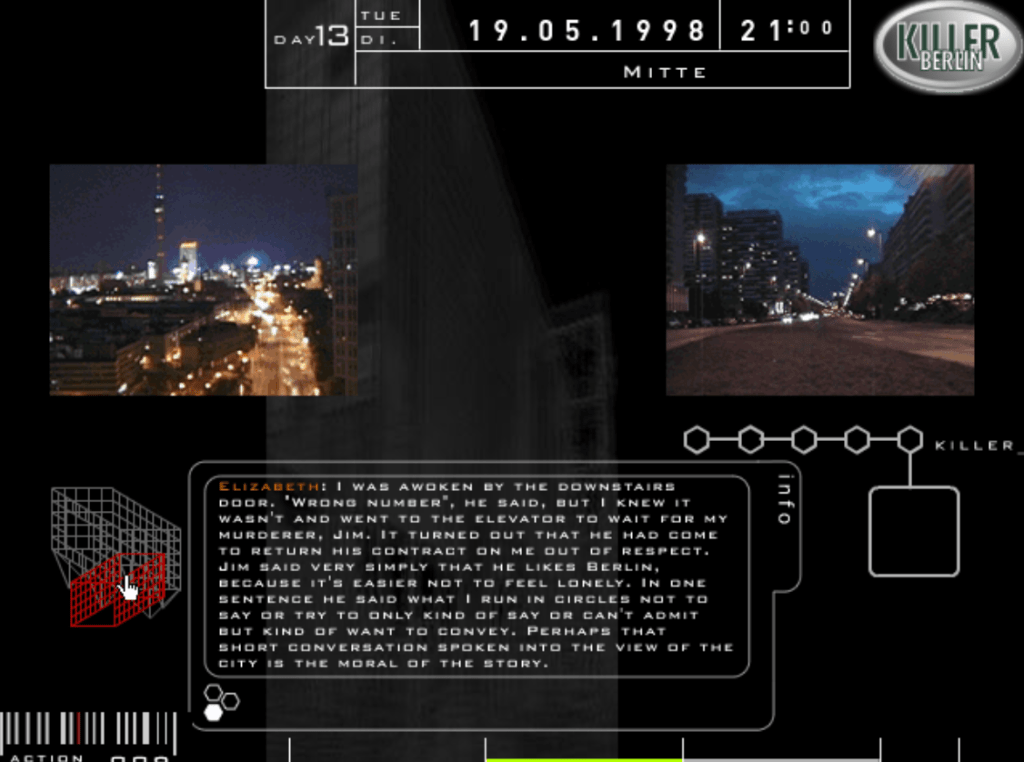

The online interactive adaptation of Killer.berlin.doc (which originally remediated the menu and navigational structure of a CD/DVD-ROM) was created using Macromedia Flash and QuickTime and is one of the first digital projects to be supported by the Media Programme of the European Union at the turn of this century.[i] The interactive version of Killer.berlin.doc turns the viewer into an active user by offering multiple ways of navigating the feature film’s content and extra material, including tracking each player’s daily activity on a map and exploring each player’s private journals in a non-sequential order. Like Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998), the film capitalizes on the 1990s hype surrounding emerging interactive media technologies while also maintaining ties with the past and with traditional modes of historiography. In all its media iterations, Killer.berlin.doc marks the time when cinema’s emerging digital ontology was entering a transitional and disputed phase, just as itconceptually charts the contested territory of transnational identity during a period of multiple levels of transition.

[i] The interactive version was located here http://killer-berlin-doc.de, but unfortunately the website was taken down in 2020. You can still access the film’s original website with some interactive features here: http://www.duplox.org/dogfilm/killer2e.html

Student responses to the feature-length and interactive versions:

“In Killer.berlin.doc, we got into some pretty interesting territory about how this 1999 docu-fiction plays with themes like surveillance, detachment, and nostalgia. It’s all about a group of Berliners playing a game of “killer,” where they have to track and “kill” each other in the city, which feels very much like it’s commenting on life in post-reunification Berlin. What’s cool is that even though this film is over two decades old, it connects really well with stuff we’ve been talking about around algorithms, interactive media, and how tech shapes the way we experience stories and cities.

First off, the surveillance. The whole interactive experience these people are playing is about constantly watching each other and being watched, which feels eerily close to our lives now with how much tech monitors us. It’s a perfect metaphor for the surveillance culture we live in today, where everything we do online is tracked. Watching the film, you get the sense that the players are both in control (they’re the ones stalking their targets), but also not, because they know they’re always being hunted too. There’s a sense that people are part of a system that’s bigger than them, and they can’t fully escape it.

Then, there’s the detachment that comes from being part of a city like Berlin. The players in the film start off pretty engaged with the game, but as things go on, you can see how they start to disconnect from each other. Everyone’s watching their back, and there’s no trust left. The city itself seems cold and hostile, kind of like what we saw in Late Shift where the main character talks about how life is just a series of meaningless events. Both of these works show how city life can make you feel isolated, like you’re constantly on guard and disconnected from others. It’s like the city turns people into strangers, even when they’re close to each other.

What’s really interesting is how the film handles nostalgia. A lot of the players talk about how Berlin has changed and how they miss the way it used to be. They’re nostalgic for a quieter, more familiar city that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s this weird mix of comforting and unsettling because while you’re looking at your past, you’re also being watched and tracked by the very technology that lets you go back. In both cases, there’s this feeling that you can never truly return to the past—everything’s changed, and you’re stuck in the present, missing what used to be.

What I think is really cool about Killer.berlin.doc is how it kind of predicts the rise of algorithm-driven media, where the narrative is all about data and algorithms shaping the story, this film plays with the idea that people are part of a system bigger than themselves. The players are stuck in roles that force them to act in certain ways, kind of like how we interact with technology today. It’s not just about human decisions anymore—algorithms, data, and systems are starting to take over, and that really shifts how we think about control and storytelling.” – Xulun Luo

“I would like to continue the reflection on space for Killer Berlin. I find that Berlin as the setting for the film is significant not only because, like any modern metropolis, it carries an inherent sense of uncertainty and disconnection, but also because Berlin, in particular, is a space of blurred boundaries and historical reconfiguration. (This nostalgia for Berlin often appears in the characters’ dialogue.) Even before any plot unfolds, this imbues the film with a Noir quality: characters navigate this fragmented, unstable space, where only through constant observation and surveillance can they construct the cognitive mapping of the city.” – Zhongwen Li

“KillerBerlin.Doc (both film & game) emulates the hollow gamic qualities of modern urban life. Ten participants are randomly assigned to kill one another, anonymously stalking their victim while in the pervasive fear of being watched. Some of them carry cameras, willingly logging their daily observations to reveal immensely personal details about their routine. The documentary film engages us in a similar voyeurism, joining each participant as they stalk one another In the CDRom, we see fragments of these events seen in the documentary, but presented in a forensic archive of all the data collected on the game’s outcomes. We peer through this diary of stalking and moments of personal intimacy, interpolating connections between the characters and the city alive and well in the background.

The work juxtaposes the hollow frames of Berlin’s new facades, detaching itself from the historical aura which made Berlin into the “Global City” it was in the first place. In the film, various partakers speak to the cities dead spaces, ruins of something prior. Most notably, the monument speaking to the freeing of Berlin’s harsh past is a ruin in of itself. Stripping through the city are empty spaces and occasional markers of the impositional Berlin wall, supposedly key to Berlin’s history. In KillerBerlin, the wall simply serves as a landmark to situate the participants’ murderous activities.

This empty presence of Berlin despite its eminence reflects – the contemporary homogenization of international urban spaces. Each of these characters had their reasons to transplant into Berlin, never having an authentic experience of the cities’ true spaces. For instance, Eisener, emanating from Tokyo, describes the city to be “provisional” in size – contrasting with Caspar’s comparison of Berlin to New York or Paris. Their descriptions dissolve any actual quality regarding Berlin, equally flat in historicity as the city’s dead spaces and cacophony of glass skyscrapers. All that matters to these participants is they partake in this game in Berlin, trailing throughout these spaces in sole focus of playing the game of Killer.

In observing each other, an equally flat description occurs in attempting to parse out who their targets are – and paranoid of being observed. This game generates a vicious cycle where surveillance alien to the spaces of Berlin lead the participants never to engage with their surrounding locality – always seeking to define others, and themselves within this social ring of strangers to the city. The choice of ingratiating the game with murder , as the deaths recounted in the game reflect a desire to no longer participate. The deaths happen beyond the frame of the game nor the documentary, reflecting they are disposed of being surveilled once they no longer exist. This dark inflection implicates the ethics of surveilling, – with the game begging the viewer to ask – what is Killer? What does it mean in Berlin today? Is it bloody murder, and is it rightful for it to occur outside of the camera.” – Loke Zhang-Fiskesjö

Read student essays on Killer.berlin.doc:

- “Killer.Berlin.doc, The Wilderness Downtown, and Late Shift: Surveillance, Detachment, and Nostalgia” by Eugene Hu

- “Urban Spaces Reflected in Interactive Art” by Julia Tinneny

- “Dis(location): the death of locality in the face of a global Berlin – KillerBerlin Media Archaeology” by Loke Zhang-Fiskesjö

Below: Choose your player – interactive menu

Want to do an even deeper dive? More screenshots below!

CREDIT: Bettina Ellerkamp, Jörg Heitmann, and home productions GmbH, 1999.