Zoe Beloff’s Beyond (1997)

In Zoe Beloff’s BEYOND, she experiments heavily with the notion of memory, ghosts, seance, and the historical timeline of technology and media. In the write-up for this work, Beloff addresses the growing wonder and partly supernatural mystique behind emerging technology. However, with the creation of new technology, Beloff also addresses its approaching, and likely inevitable, usage for mass destruction. The project has an extremely eerie tone, reminiscent of modern horror computer games. Although there’s no monster waiting for you behind the corner in BEYOND, there are certainly ghosts.

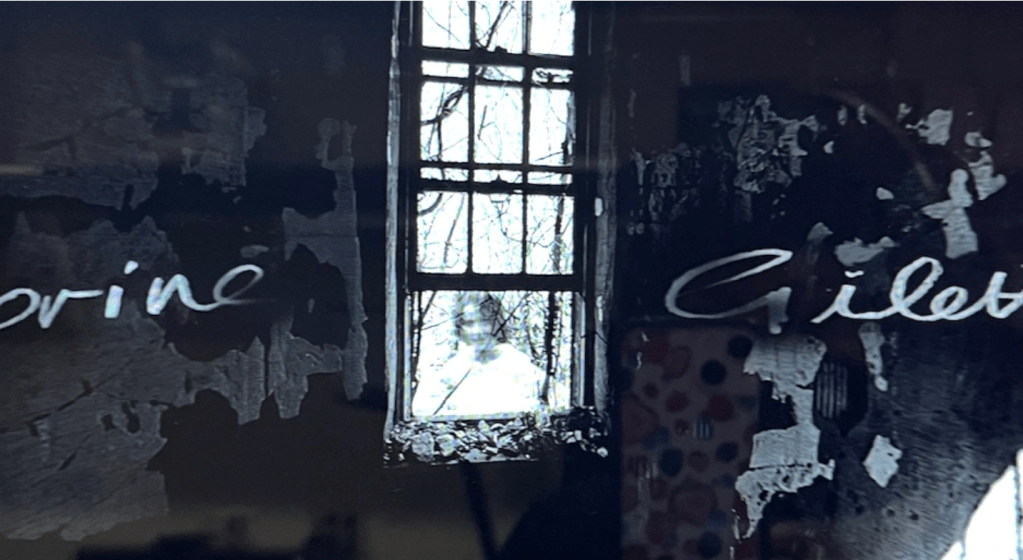

These ghosts manifest in a literal sense with Spirit photos appearing on building walls and the outline of phantoms in windows, but also metaphorically, within the structure of the project itself (the ancient panorama), and a library of old film, reworked with music and performances by Beloff herself. The culmination of the ghosts, the uncanny, and the uncomfortable reflection of circularity in time, results in an interactive work that makes the user feel disoriented and unsettled. While Beloff’s WHERE WHERE THERE THERE WHERE relies more on moving images in the panorama, BEYOND requires users to sit with its unsettling images and descriptions. The music in BEYOND adds an additional displacing element, causing a greater sensory experience with the sharp sound of wind and breaking glass in the panorama contrasting with more traditional, cinematic music used in the mini films.

As a work of Media Archaeology, BEYOND embodies Artist and Scholar Maryam Muliaee’s description of the practice from her essay “Media Archaeology and Art: An Exploration of Past, Present, and Future” saying, “With its focus on uncovering, analyzing, and re-contextualizing forgotten, obsolete, and overlooked media technologies, media archaeology offers artists a wide repository of materials and ideas”(Muliaee 2). Muliaee continues, “Artists repurpose and remake old and new technologies in parallel lines, and their works can provide fresh perspectives on the present by reflecting on the past” (Muliaee 2). This framework describes a guiding practice not only for BEYOND but also for many other Beloff works.

In a 2015 YouTube video for The MET, Beloff describes the necessity of looking to artwork of the past to understand and address the modern problems of our world. Using the specific example of Eduard Manet’s work depicting armed labor struggles in France, Beloff addresses these cyclical complexities. In her work, Beloff acknowledges systems such as capitalism and the industrial war complex, which affect the way in which history is depicted and communicated. In BEYOND specifically, Beloff addresses what Baudelaire calls a “‘city full of dreams where ghosts accost the passers-by in broad daylight,’” (Beloff 2) confronting users of the work with the uncanny, magic, and precedent for everyday technology. Furthermore, the work addresses the apprehension of new technology, with its position between the scientific and the supernatural.

With BEYOND, Beloff attempts to address a wider understanding of society’s relationship to emerging media, taking a “spontaneous” (Beloff 2) approach to sourcing materials and shaping the work overall. The pictures and photos used in the panorama are not of famous historical figures but are rather abstract, sometimes even distorted versions of once clear faces. In the write-up for her work, Beloff asks, “If something which we now take for granted like photography was experienced as an uncanny phenomena which seems to undermine the unique identity of objects, creating a parallel world of phantasmal doubles, then the possibility of the production of say Spirit Photographs was not nearly as implausible as it might today” (Beloff 6). Here Beloff addresses the gap in certainty behind the new, similar to the gap of a secular understanding of technology that’s now considered old.

When one revisits ghosts (be that of history, technology, or forgotten media) what is made of the supposed progress in society? Beloff continues to describe BEYOND as “a study between the relationship between imagination and technology”, with a virtual alter-ego of herself appearing as “the interface between the living and the dead” with the avatar transmitting “movies that record her impressions” (Beloff 1). Though the mini films throughout the project address philosophical theories behind the progress of technology, the high concept of the work requires long study, revisitation, and possibly a desire to get to the “truth” of the past. Though the mini-films are linked by ideas, comprehensive understanding of the theories discussed requires much further exploration to understand what supposedly went wrong. Although we know no one lives forever, with the combination of expanded old media and the willingness to address them, perhaps ideas will. But will the supposed progress from reflecting on ghosts, or creating a work of media archaeology more broadly, actually change our outcome? While users of BEYOND confront decades of fear, technology, and magic, in one panoramic experience, what lies beyond the theory and path of emerging technology is much more unsettling than any ghost.

Works Cited

Beloff , Zoe. “The Dream Life of Technology.” Zoebeloff.Com, Jan. 1997, http://www.zoebeloff.com/beyond/dreamlife.pdf. Accessed Oct. 2024.

Muliaee, Maryam. “Media Archaeology and Art: An Exploration of Past, Present, and Future.” The Journal of Media Art Study and Theory, vol. 5, Aug. 2024, pp. 2–12.

“The Artist Project: Zoe Beloff.” YouTube, YouTube, 7 Dec. 2015, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QEV1hxN375o.

BEYOND Analysis: Ayisat Bisiriyu

The Influencing Machine of Natalija A.(2013)

Zoe Beloff’s The Influencing Machine of Natalija A. is a haunting, multi-dimensional installation that brings viewers into the disturbing inner world of Miss Natalija A., a psychiatric patient from the early 20th century. Beloff’s work, rooted in Victor Tausk’s analysis of “influencing machine” delusions, serves as both an immersive exploration of Natalija’s fractured reality and a broader critique of societal power dynamics, media influence, and gender norms.

At the heart of The Influencing Machine is Natalija’s delusion that external forces are manipulating her thoughts and body through a mysterious “electrical apparatus,” controlled by male doctors. This machine, however, transcends its role as a symptom of schizophrenia; it operates as a metaphor for the societal forces that shape and control individual identity, particularly through enforced gender norms and sexual expectations. Beloff, drawing on Viktor Tausk’s perspective that machines are “unconscious projections of man’s bodily structure,” suggests that Natalija’s hallucinations symbolize a broader societal attempt to dominate and constrain individuals, with the “machine” functioning as an embodiment of cultural systems, such as Nazism or traditional gender roles, that press individuals into conforming to collective norms.

Beloff’s portrayal of male operators managing a female patient highlights the gendered dynamics of power and surveillance. The male doctors’ intrusive, objectifying gaze reflects Natalija’s psychological experience of her body and autonomy being breached, evoking Laura Mulvey’s concept of the “male gaze,” wherein the female form is subjected to scrutiny, manipulation, and control, leaving her vulnerable and passive. Natalija’s perceived lack of agency and constant surveillance echo Michel Foucault’s notion of the “panopticon,” a metaphor for societal surveillance that pressures individuals to internalize control over themselves. In this way, Natalija’s sense of being watched, prodded, and influenced parallels the way Foucault describes the panoptic mechanism, where the mere possibility of surveillance induces self-regulation.

Beloff’s aesthetic, layered with eerie animations and sounds, builds a Gothic, haunting atmosphere that immerses the viewer in Natalija’s experience. The feeling of an “unseen” force orchestrating events aligns with Foucault’s theories of surveillance and power structures, further emphasizing the psychological toll of feeling observed and controlled. The Gothic mood, combined with the audience’s exploration of Natalija’s fragmented narrative, invites viewers to participate in a form of invasive observation, not unlike the controlling “gaze” Natalija believes exerts influence over her. This interaction with her fragmented psyche mirrors the controlling forces that haunt her, tying into both Foucault’s panopticon and Mulvey’s gaze theory by merging the thematic with the experiential. Through this approach, Beloff implicates viewers as participants in the surveillance that entraps Natalija, blending form and content to reinforce the unsettling dynamics of control and vulnerability that drive The Influencing Machine.

Beloff’s work delves into the anxieties surrounding early 20th-century media technologies, such as radio and television, which seemed to wield an almost supernatural influence over human thoughts. By framing Natalija’s delusions within this historical context, Beloff connects her character’s paranoia to the collective cultural fears of mind control and media influence, underscoring the eerie ways in which media can feel invasive. Through an interactive installation, participants are invited to “operate” elements of Natalija’s imagined machine, blending the viewer’s agency with Natalija’s perceived loss of control. This immersive design directly evokes Marshall McLuhan’s theory that media act as extensions of the self, intruding into our consciousness in ways that can feel coercive or even uncanny.

In her exploration, Beloff draws extensively from Viktor Tausk’s psychoanalytic theories, particularly his concept of the “influencing machine,” to examine how media technologies were thought capable of reshaping minds. By embodying this idea in the early technological forms of radio and telegraphy, Beloff situates Natalija’s fears in an era rife with anxieties over technology’s reach and manipulative potential. The piece, steeped in Freudian themes of the uncanny and alienation, brings these anxieties to life as Natalija’s fictional machine represents a broader cultural unease about media’s invasive potential. Through the interactive nature of the installation, each user click offers a visceral encounter with these fears, making McLuhan’s ideas about media extensions more than theoretical as participants confront the machine’s reach into Natalija’s psyche—and perhaps their own.

A particularly haunting aspect of The Influencing Machine is its portrayal of Natalija’s alienation from her own body, which Tausk describes as feeling “alien” to her. Natalija’s psyche projects her genitalia and other body parts onto the outer world, transforming her physical self into something foreign and grotesque. This disturbing distortion can be interpreted as a response to societal pressures around heteronormativity and femininity, which often cause individuals to feel estranged from their own bodies. Beloff suggests that Natalija’s experience of body dysmorphia reflects how rigid societal norms—especially those related to gender—can alienate people from their natural identities.

“There is no one character that represents her. In my mind she could be found in any number of the women in these films. Thus her condition becomes generalized, spreading through the population at large,” – Zoe Beloff

Beloff’s installation invites participants to engage directly with Natalija’s world, using a pointer to explore different parts of the “machine” and trigger scenes that evoke 1920s-30s Germany. This interactive component of The Influencing Machine of Natalija A. involves users in Natalija’s paranoia, positioning them as both spectators and operators, much like the doctors she distrusts, and implicating them in her sense of being watched. Beloff enhances this sense of psychological immersion by using a Phantogram, a 3D illusion requiring stereo glasses, which mirrors Natalija’s fragmented view of reality. This choice reinforces her isolation, as only one person at a time can fully see her hallucinations, creating a visceral metaphor for the loneliness and disconnection of mental illness.

Beloff’s use of interactive cinema techniques supports the multimedia format, presenting her work as a non-linear “book” of animated, clickable elements that guide users through different facets of Natalija’s paranoia and belief in a controlling machine. This format aligns with Lev Manovich’s concept of the “database narrative,” where the story’s structure allows users to navigate through fragments rather than a linear storyline. This interactivity not only deepens the viewer’s emotional connection but also reflects Natalija’s disjointed thought process, making the experience itself a mirror of her psychological struggle. By inviting participants to explore her fragmented narrative, Beloff creates an interactive, immersive environment that captures the overwhelming isolation and pervasive fear central to Natalija’s reality.

“…I wanted to allude to the development of real influencing machines, in the form of radio and television in 1930’s Germany, extending the definition of psychosis from the individual to society,” – Zoe Beloff

Beloff’s The Influencing Machine goes beyond Natalija’s individual experience of psychosis, using her delusion as a larger metaphor for society’s collective susceptibility to media’s persuasive power. By layering her hallucinations with images of Nazi propaganda and early medical footage, Beloff presents the “influencing machine” as more than a symptom of schizophrenia; it becomes a reflection of societal vulnerability to technological manipulation. In an age preoccupied with media’s influence—from early radio broadcasts to contemporary surveillance practices—Beloff’s work underscores the delicate balance between technological benefits and the potential for control.

Through this lens, The Influencing Machine of Natalija A. becomes a layered exploration of autonomy, mental illness, and the pervasive reach of media, capturing the unsettling power of technology to mold minds, enforce gender norms, and even influence entire societies. It stands as a Gothic, immersive reflection on control—both from external pressures and internal conflicts—and reveals the way media not only shapes perceptions but also shapes identities. By simulating Natalija’s experience of an “influencing machine,” Beloff critiques the subtle psychological control modern media wields over individuals, illustrating how societal expectations, technological advances, and mental health struggles can all impact one’s sense of autonomy. In this context, the piece serves as a profound commentary on how media technologies shape self-perception and personal agency. Beloff’s portrayal of the blurred line between viewer control and Natalija’s lack of control reveals the unsettling boundary between individual autonomy and the potential for media-driven manipulation.

References

Beloff, Z. (2013). The Influencing Machine of Miss Natalija A. Christine Burgin Press.

Tausk, V. (1919). On the Origin of the “Influencing Machine” in Schizophrenia. In Psychiatric Quarterly, 3(2), 97–111.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill.

Cartwright, L. (1995). Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Beloff, Zoe. (2001). The Influencing Machine of Natalija A. Electronic Literature Directory, directory.eliterature.org/individual-work/316.

Archive of Digital Art. “The Influencing Machine of Miss Natalija A. by Zoe Beloff.” Archive of Digital Art, http://www.archive-digitalart.eu.

Foucault, Michel. (1995). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan, Vintage Books.

Manovich, Lev. (2001). The Language of New Media. MIT Press.

The Influencing Machine of Natalija A Analysis: Sabrina Smith